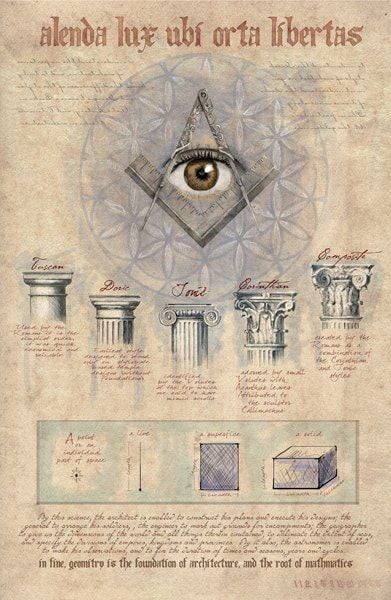

Alenda Lux Ubi Orta Libertas, translated from Latin meaning “Let Learning Be Cherished Where Liberty Has Arisen"

A point, a line, a plane, a solid; a fundmental principle of geometry.

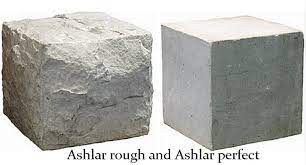

Ashlar rough and Ashlar perfect are not just two pieces of stone but a clear representation of what we’ve and what we hope to be. They symbolize Man’s moral and spiritual life.

Ashlars are a representation of the very beautiful symbol. The rough and perfect ashlars bear the same relation to each other as ignorance does to knowledge, death to life, and light to the darkness. Ashlar rough (rude, natural stone), which masonically, is a symbol of men’s natural state of ignorance and a symbol of the profane world. Ashlar perfect is already prepared (hewed, squared, polished and smooth) and as such it’s used in the building. It’s a symbol of the state of perfection attained by means of education.

In essence, in Freemasonry, it means that by means of education and the acquirement of knowledge, a man, who begins as Rough Ashlar (an imperfect stone) improves the state of his spiritual and moral being and becomes like Perfect Ashlar and makes the final journey to the Grand Lodge Above. He may leave behind a reputation as a wise counselor, a pillar of strength and stability, a Perfect Ashlar on which younger Masons may test the correctness and value of their own contribution to the Masonic order.

Ashlar etymology

The word is attested in Middle English and derives from the Old French aisselier, from the Latin axilla, a diminutive of axis, meaning "plank". "Clene hewen ashler" often occurs in medieval documents; this means tooled or finely worked, in contradistinction to rough-axed faces.

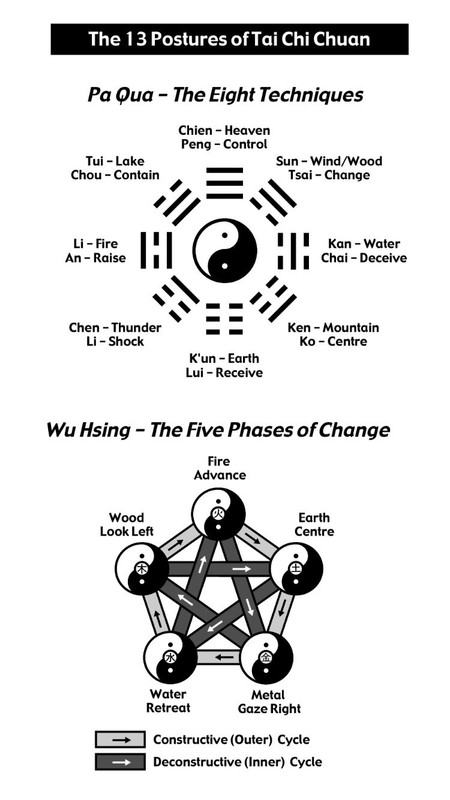

The Chinese word "Pu" is often translated as "the uncarved block," and refers to a state of pure potential which is the primordial condition of the mind before the arising of experience. The Taoist concept of Pu points to perception without prejudice, i.e. beyond dualistic distinctions such as right/wrong, good/bad, black/white, beautiful/ugly. It is a state of mental unity which places the Taoist practitioner into alignment with the Tao.

The principle of Pu had political overtones at some points in Chineses history. During the Warring States period (485 to 221 BCE), for example, in opposition to the Confucianist championing of intrusive manipulative government, as represented by the elaborate carving of jade into intricate shapes, early Taoists championed the idea of a simple, hands-off "uncarved block of wood" approach to government. Closely connected to this was the idea of Wu Wei--effective action through non-action. To Taoists, good government and ethical life involved not exercising human willpower over one's self and others, but in quiet acquiescence to the power of the Tao.

Reninger, Elizabeth. "A Definition the Term "Pu" in Taoism." Learn Religions, Jan. 1, 2021, learnreligions.com/definition-of-pu-3182628.

Terminology

Pu can be written with either of the variant Chinese characters 樸 or 朴, which are linguistically complex.

Characters

Both 樸 and 朴 are classified as radical-phonetic characters, combining the semantically significant "tree" radical 木 (commonly used for writing names of trees and wooden objects) with the phonetic indicators pu 菐 or bu 卜.

The Chinese character pu 樸 was first recorded on Chinese bronze inscriptions from the Spring and Autumn period (771-476 BCE), and the character pu 朴 was first recorded in Chinese classics from the Warring States period (475-221 BCE).

When the People's Republic of China promulgated simplified Chinese characters in 1956, the established variant pu 朴 (with 6 strokes) was chosen to replace the traditional Chinese character pu 樸 (with 16 strokes).

One of the two (c. 168 BCE) Mawangdui silk manuscript versions of the Daodejing, discovered in 1973 by archeologists excavating a tomb, uses a rare textual variant character for pu 樸: wò 楃 "a house tent (esp. with a wooden roof)", written with the "tree radical" and wu 屋 "room; house" phonetic. The "B" text, like the received version, uses pu 樸 8 times in 6 chapters; the "A" text uses wò 楃 6 times in 4 chapters and has lacunae in chapters 19 and 57. The (c. 121 CE) Shuowen jiezi defines wo 楃 as muzhang 木帳 "wood canopy", and the (early 3rd century) Guangya defines it as choumu 幬幕 "curtain; cover". These variant words pú - *phrôk 樸 "unworked wood" and wò - *ʔôk 楃 "house tent" are semantically and phonologically dissimilar.

PU TAO - PTAH

BU DAO - BUDDA

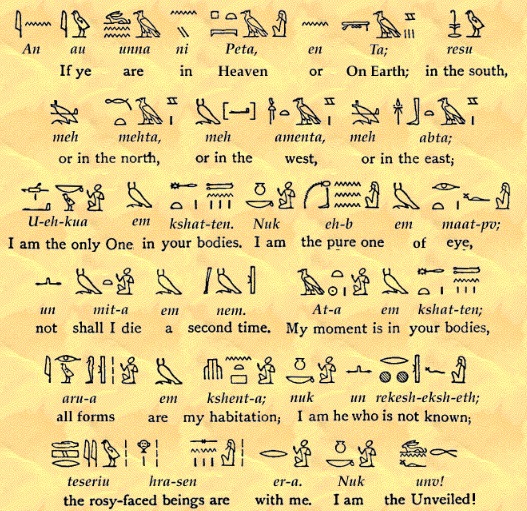

Thrice-Greatest Hermes, Vol. 1, by G.R.S. Mead, [1906], at sacred-texts.com

Rough translation (from French):

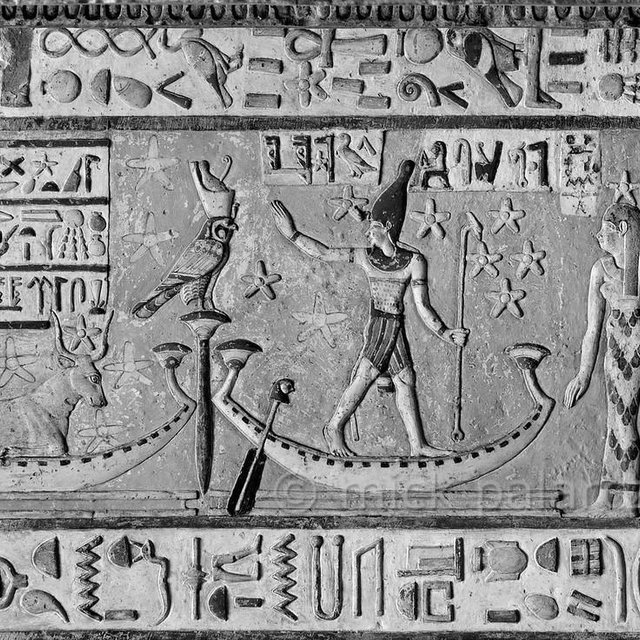

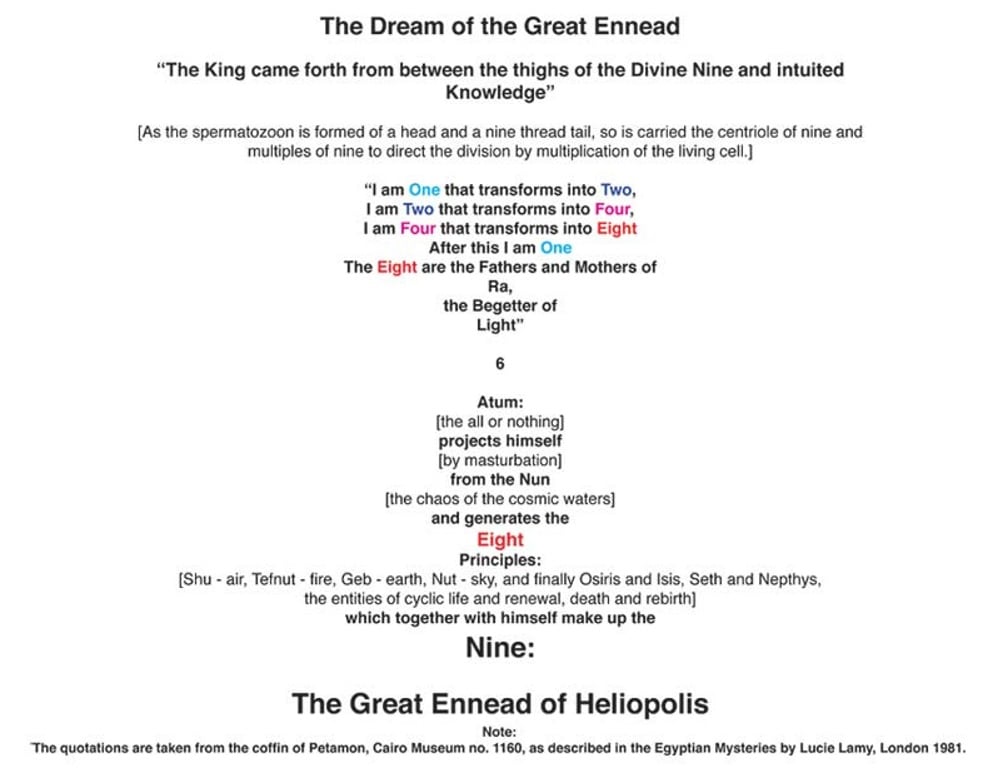

It is Pétamôn, himself, who tells us: "I am one which becomes two, I am)) TWO which becomes four, I am four which becomes eight, I am one after that,)) I am Khopri in Hait-berborou, I am Osiris in Khonit, I am Hâpi begotten)) of Phtah, I am this creator Râ, father of Shouî Give me, give me, Aries »jumper, give me that no evil assails the body of TOsiris. . . Petamon. Some points are doubtful in the translation, which relates to aa / wna daîni, where I see the form m ^ with the W, equivalent of n? ^, And the | -m ^, where Ton could translate: A / W ^^ A C_l y ^ l ^ û i ^^ - ^ "I am ONE in his of him" which is by itself this force which maintains the life and the power of the gods. The only issue I want to draw attention to is digital progression. It was a question of identifying the deceased with the ennëade conceived as formed of the ogdoade plus one. One who becomes two, it is Rà who has drawn from himself, by the process we know, the Shou-Tafnouit couple. Two which becomes four, it is the production of the four male gods who support the world, Heh, Naou, Kakou, Amonou, and which are engendered by the separation of Sibou and Nouît at the moment when Shou separates the sky and the earth which are the result of Sibou and Nouît. Four which becomes eight, it is the duplication of these four characters in couples, Hehou-Heliit, Naou-Naouit, Kakou-Kakouit, Amon-Amaunit. Finally, one who comes after him, that is to say after four who IS EIGHT, is the supreme leader, the one who, being added to Togdoade, transforms her into an ennead, that is to say the god Amonrâ of Tlièbes, in which are summed up all the gods listed below, Khopri, Osiris, Hâpi, Râ, the ram of Amun and Osiris.