Dragonfish, also called sea moth, any of about five species of small marine fishes comprising the family Pegasidae and the order Pegasiformes. Dragonfish are found in warm Indo-Pacific waters. They are small (to about 16 centimetres [6 1/2 inches] long), elongated fish encased in bony rings of armour. The armour is fused on the head and body but not on the tail, which is thus flexible. The pectoral fins are large, horizontal, and winglike; the pelvic fins consist of a few fingerlike rays. The mouth is small and toothless and is placed below an elongated, bony snout.

Little is known about the natural history of the dragonfish. Their relationships to other fish groups are also in doubt. One of the best known dragonfish is Pegasus volitans, a blue-eyed, brown or deep-red fish found from India to Australia.

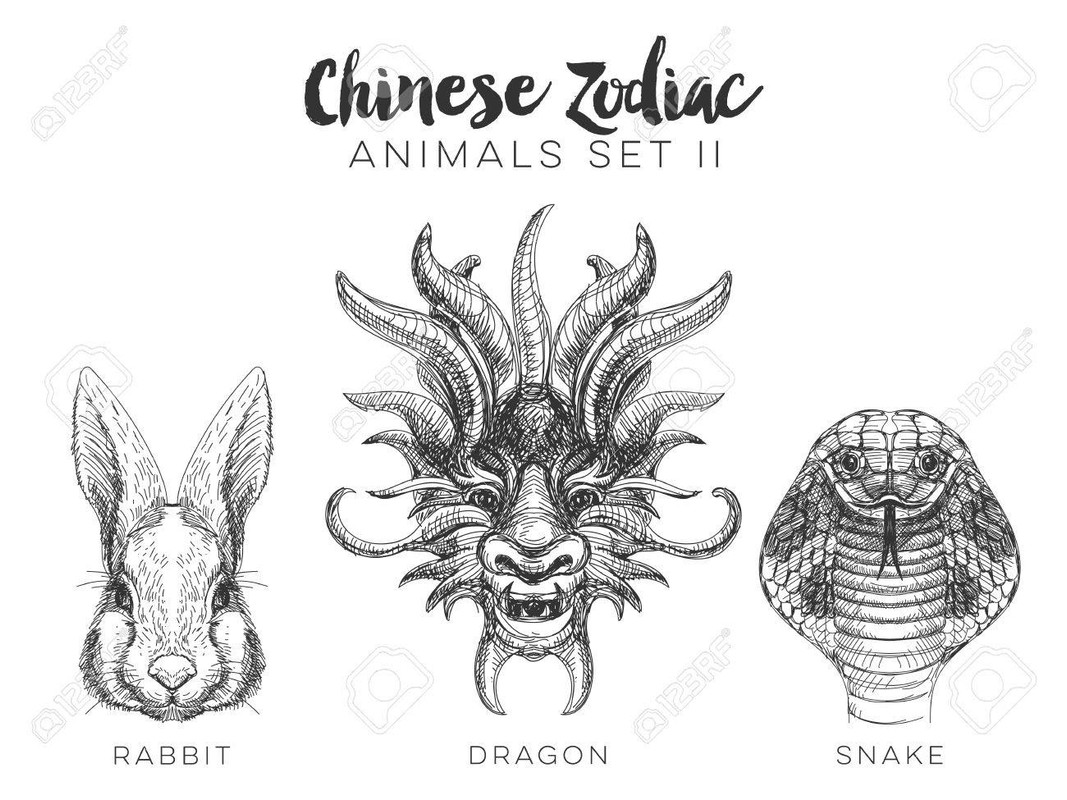

Ryūjin (龍神), which in some traditions is equivalent to Ōwatatsumi, was the tutelary deity of the sea in Japanese mythology. In many versions Ryūjin had the ability to transform into a human shape. Many believed the god had knowledge on medicine and many considered him as the bringer of rain and thunder, Ryujin is also the patron god (ujigami) of several family groups.

This Japanese dragon, symbolizing the power of the ocean, had a large mouth. He is considered a good god and patron of Japan, since the Japanese population has for millennia lived off the bounty of the sea. Ryūjin is also credited with the challenge of a hurricane which sank the Mongolian flotilla sent by Kublai Khan.[citation needed] Ryūjin lived in Ryūgū-jō, his palace under the sea built out of red and white coral, from where he controlled the tides with magical tide jewels. Sea turtles, fish, jellyfish, snakes, other sea creatures are often seen as Ryūjin's servants.

Mythology

How the jellyfish lost its bones

One legend involving Ryūjin is the story about how the jellyfish lost its bones. According to this story, Ryūjin wanted to eat monkey's liver (in some versions of the story, to heal an incurable rash), and sent the jellyfish to get him a monkey. The monkey managed to sneak away from the jellyfish by telling him that he had put his liver in a jar in the forest and offered to go and get it. As the jellyfish came back and told Ryūjin what had happened, Ryūjin became so angry that he beat the jellyfish until its bones were crushed.

The Tale of Tawara Tōda

Further information: Tawara Tōda Monogatari

One myth involves Ryujin asking a man by the name of Tawara Tōda to help him get rid of a giant centipede attacking his kingdom. Tawara Tōda agrees to help Ryujin and Tawara Tōda accompanies Ryujin back to his home. When Tawara Tōda killed the centipede Ryjuin awarded him with a bag of rice.[5]

Empress Jingu

According to legend, the Empress Jingū was able to carry out her attack into Korea with the help of Ryūjin's tide jewels. Some versions of the legend say that Empress Jingū asked Isora to go down to Ryujin's palace and retrieve the tide jewels.[6]

Upon confronting the Korean navy, Jingū threw the kanju (干珠, "tide-ebbing jewel") into the sea, and the tide receded. The Korean fleet was stranded, and the men got out of their ships. Jingū then threw down the manju (満珠, "tide-flowing jewel") and the water rose, drowning the Korean soldiers. An annual festival, called Gion Matsuri, at Yasaka Shrine celebrates this legend.

Family

Ryūjin was the father of the beautiful goddess Toyotama-hime who married the hunter prince Hoori. The first Emperor of Japan, Emperor Jimmu, is said to have been a grandson of Otohime and Hoori's. Thus, Ryūjin is said to be one of the ancestors of the Japanese imperial dynasty.

Worship

Ryūjin shinkō (竜神信仰, "dragon god faith") is a form of Shinto religious belief that worships dragons as water kami. It is connected with agricultural rituals, rain prayers, and the success of fishermen.

The god has shrines across Japan and especially in rural areas where fishing and rains for agriculture are important for local communities.[2]

Ryujin - Wikipedia

Dagon (Phoenician: 𐤃𐤂𐤍, romanized: Dāgūn; Hebrew: דָּגוֹן, Dāgōn), or more accurately Dagan, (Sumerian: 𒀭𒁕𒃶, romanized: dda-gan[1]) was a god worshiped in ancient Syria across the middle of the Euphrates, with primary temples located Tuttul and Terqa, though many attestations of his cult come from cities such as Mari and Emar as well. In settlements situated in the upper Euphrates area he was regarded as the "father of gods" similar to Mesopotamian Enlil or Hurrian Kumarbi, as well as a lord of the land, a god of prosperity, and a source of royal legitimacy. A large number of theophoric names, both masculine and feminine, attests that he was a popular deity. He was also worshiped further east, in Mesopotamia, where many rulers regarded him as the god capable of granting them kingship over the western areas.

Attestations of Dagan from coastal areas are much less frequent and come mostly from the northern city of Ugarit, where Dagan's cult had a limited scope. According to the Hebrew Bible, Dagan was also the national god of the Philistines, with temples at Ashdod and Gaza, but there is no extrabiblical evidence confirming this.

Etymology

Multiple origins have been proposed for Dagan's name.

According to Philo of Byblos, the Phoenician author Sanchuniathon explained Dagon as a word for "grain " (siton).[2] Historian Manfred Hutter considers it possible that the god's name derives from the root *dgn (to be cloudy), which he interprets as a sign that he was originally a weather god.[3] However, the notion of Dagan being a weather god is rejected by most researchers of this deity (see the Dagan and weather gods section below).

Lluís Feliu in his monograph The God Dagan in Bronze Age Syria rejects both of these theories and concludes that Dagan's name originated in a pre-Semitic language spoken in inland Syria.[4] This theory is supported by Alfonso Archi as well.[5] Multiple other ancient Syrian deities are regarded as originating in such a substratum, including Aštabi, Ishara and Kubaba.[6][7][8][9]

The association with a Hebrew word for "fish" (as in Hebrew: דג, Tib. /dɔːg/) in medieval exegesis has led to an incorrect interpretation of Dagan as a fish god.[2]

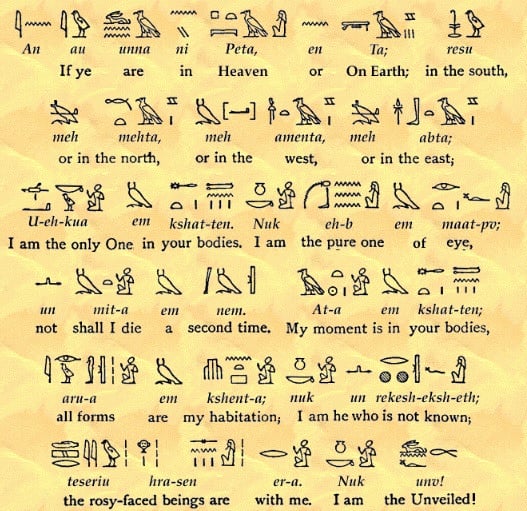

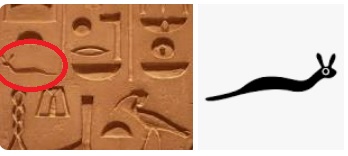

The Hare Goddess Wenet

When we think of Easter, the “Easter Bunny” is a main topic for festivity and play. In ancient Egypt, the rabbit, or hare, was the Goddess Wenet. The Egyptians venerated the hare because of its swiftness and keen senses. The hare’s form was also taken by other deities who had associations with the Otherworld. In one scene from the Egyptian Book of the Dead, a hare-headed god, a snake-headed god, and a bull-headed god sit side by side; a hare-headed deity also guards one of the Seven Halls in the Underworld.

Wenet is further described in a portion of spell 17 of the Book of the Dead, which reads: “…Who is he? ‘Swallower of Myriads’ is his name, and he dwells in the Lake of Wenet…” To interpret the meaning of this passage, one remembers that hares can swim, and the Egyptian creation first came about in the watery abyss of Nun, out of which rose the primordial mound where newly born gods manifested. To “dwell in the Lake of Wenet” means to live renewed, revitalized, to be reborn, to live, forever and ever, renewed after death, as the god Atum-Re. Spell 17 goes on to identify the dweller in the Lake of Wenet as Atum-Re, the creator of all, whose father is said to be Nun, because he rose out of the “watery abyss.”

Other passages in the Book of the Dead mention Wenet. Spell 149 describes the “Mound of Wenet” though which the spirit travels to be reborn, rejuvenated while in the Otherworld or Duat:

“…As for that Mound of Wenet which is in front of Rosetjau, its breath is fire, and the gods cannot get near it, the spirits cannot associate with it; there are four cobras on it whose names are ‘Destruction.’ O Mound of Wenet, I am the greatest of the spirits who are in you, I am among the Imperishable Stars who are in you, and I will not perish, nor will my name perish. ‘O savour of a god!’ say the gods who are in the Mound of Wenet. If you love me more than your gods, I will be with you for ever…”

Not only is the Mound of Wenet a site of sacred creative energy, the ability of the hare to elude destruction, shows the Goddess Wenet, as associated with the hare, to provide a haven for the spirit, where it is rejuvenated on its journey through the Otherworld, a place where it cannot perish.

Ancient Egyptian Hare

“In many ancient civilizations the hare is a “lunar animal,” because the dark patches (maria, “seas”) on the surface of the full moon suggest leaping hares….In Buddhist, Celtic, Hottentot and ancient Egyptian cultures as well, the hare was associated with the moon…known for it’s vigilance and for the myth of it sleeping with it’s eyes open. The early Christian Physiologus mentions a further peculiarity of the hare: with its shorter front legs, it can run fastest uphill, eluding its pursuers…It’s speed and vigilance, according to Plutarch (AD 46 – 120), have a “divine” quality…A trickster figure, the hare outwits larger and stronger animals…For psychologically oriented symbologists, neither the speed nor the “timidity” of the hare is critical, but rather the rate at which it multiplies: this makes the animal a symbol of fertility…”

~ Biedermann, in the Dictionary of Symbolism

The Nome of Wenet, where the city of Khemenu was located, was the province of Hermopolis. The province was considered the “District of the Hare”, named after the deity Wenet.

Wenet was both the patron goddess of the area of Wenu, the 15th Upper Egyptian Nome and of the city of Thoth which is more commonly referred to as Hermopolis. These two deities are often paired in ancient Egyptian symbolism and art. Thoth is the scribe of the gods, credited with the invention of writing by the ancient Egyptians. Curiously, the hare deity in Mayan belief also invented writing.

Nature.com article - slug or horned viper?

Many ways of saying the same thing - horned, winged, plumed, crested, crowned

Handmade Wealthy Brass Dragon Fish Statue Home Decor Collectible Gift

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.