Tyr (T) and Taweret (Taw)

The sun gods are normaly written with initial s or t. The proto-Semitic phoneme /ṱ/ shifted to /ṣ/. In the Sumerian, Akkadian, Assyrian and Babylonian creation myth Enuma Elish, Anshar (also spelled Anshur), which means “whole heaven”, is a primordial god.

His consort is Kishar which means “Whole Earth”. If this name /Anšar/ is derived from */Anśar/, then it may be related to the Egyptian hieroglyphic /NṬR/ (“god”), since hieroglyphic Egyptian /Ṭ/ may be etymological */Ś/.

In Germanic mythology, Týr (Old Norse), Tíw (Old English), and Ziu (Old High German) is a god. Like Latin Jupiter and Greek Zeus, Proto-Germanic *Tīwaz ultimately stems from the Proto-Indo-European theonym *Dyeus.

Stemming from the Proto-Germanic deity *Tīwaz and ultimately from the Proto-Indo-European deity *Dyeus, little information about the god survives beyond Old Norse sources. Due to the etymology of the god’s name and the shadowy presence of the god in the extant Germanic corpus, Týr may have once held a more central place among the deities of early Germanic mythology.

By way of the process of interpretatio germanica, the deity is the namesake of Tuesday (‘Týr’s day’) in Germanic languages, including English. Interpretatio romana, in which Romans interpret other gods as forms of their own, generally renders the god as Mars, the ancient Roman war god, and it is through that lens that most Latin references to the god occur.

For example, the god may be referenced as Mars Thingsus (Latin ‘Mars of the Thing’) on 3rd century Latin inscription, reflecting a strong association with the Germanic thing, a legislative body among the ancient Germanic peoples still in use among some of its modern descendants.

Týr is the namesake of the Tiwaz rune, t-rune ᛏ, a letter of the runic alphabet corresponding to the Latin letter T. Outside of its application as a theonym, the Old Norse common noun týr means ‘(a) god’ (plural tívar). In turn, the theonym Týr may be understood to mean “the god”.

Tyr and Thor

In the Old English rune poem dated to the 8th or 9th century, the T-rune (T: Tyr, the sky god) named after Týr, and reconstructed in Proto-Germanic as *Tîwaz or *Teiwaz, is apparently associated with a circumpolar constellation, one that never sets below the horizon, and compared to the quality of honor, justice, leadership and authority.

The Old English rune poem has stanzas on 29 Anglo-Saxon runes. It stands alongside younger rune poems from Scandinavia, which record the names of the 16 Younger Futhark runes. The sole manuscript recording the poem, Cotton Otho B.x, was destroyed in the Cotton Fire of 1731, and all editions of the poems are based on a facsimile published by George Hickes in 1705.

In the poem the Tir rune appears to have adopted the Scandinavian form (Týr, the Anglo-Saxon cognate being Tiƿ). However, tīr exists as a noun in Old English, with a meaning of “glory, fame honour”. Perhaps involving the original meaning of Tiƿ, the god associated with fame and honour; also interpreted as “a constellation”, “lodestar” because of the stanza’s emphasis on “fixedness”.

The name of the Old English Þorn rune is thus the only case with no counterpart in Scandinavian tradition, where the corresponding rune is called Þurs. Thorn or þorn (Þ, þ) is a letter in the Old English, Gothic, Old Norse, and modern Icelandic alphabets, as well as some dialects of Middle English. It is transliterated as þ, and has the sound value of a voiceless dental fricative /θ/ (the English sound of th as in thing).

It was also used in medieval Scandinavia, but was later replaced with the digraph th, except in Iceland, where it survives. The letter originated from the rune ᚦ in the Elder Fuþark and was called thorn in the Anglo-Saxon and thorn or thurs (a category of beings in Germanic paganism) in the Scandinavian rune poems. Its reconstructed Proto-Germanic name is Thurisaz.

The rune ᚦ is called Thurs (Old Norse Þurs “giant”, from a reconstructed Common Germanic *Þurisaz) in the Icelandic and Norwegian rune poems. Old Norse þurs, Old English ðyrs, and Old High German duris ‘devil, evil spirit’ derive from the Proto-Germanic masculine noun *þur(i)saz, itself derived form Proto-Germanic *þurēnan, which is etymologically connected to Sanskrit turá- ‘strong, powerful, rich’.

Thurisaz (Thurs) is the rune associated with Thor, and embodies masculine energy and the combination of wisdom with force. Its energies are invoked to strengthen and direct ones Will as well as destroy barriers to positive evolution.

It’s not uncommon for the rune meaning of Thurisaz to be described as a thorn that is most sharp, a grim and evil thing to take grip on or touch. However, it is representative of Thor and his hammer, protecting Asgard from the thurses, giants who resist the expansion of consciousness throughout the multiverse.

In every respect, the energies of Thurisaz are a forceful enemy of unconsciousness, ignorance and the rule of brute violence. Thurisaz represents the warrior that combines consciousness and wisdom with matters requiring force. Thor is the champion god of courageous and free human beings and the ultimate physical fighting force.

The name is derived from Old English Þūnresdæg and Middle English Thuresday (with loss of -n-, first in northern dialects, from influence of Old Norse Þorsdagr) meaning “Thor’s Day”. It was named after the Norse god of Thunder, Thor. Thunor, Donar (German, Donnerstag) and Thor are derived from the name of the Germanic god of thunder, Thunraz, equivalent to Jupiter in the interpretatio romana.

The English name is derived from Old English Tiwesdæg and Middle English Tewesday, meaning “Tīw’s Day”, the day of Tiw or Týr, the god of single combat, and law and justice in Norse mythology. Tiw was equated with Mars in the interpretatio germanica, and the name of the day is a translation of Latin dies Martis.

Taw

Taw, tav, or taf is the twenty-second and last letter of the Semitic abjads, including Phoenician Tāw. The Phoenician letter gave rise to the Greek tau (Τ), Latin T, and Cyrillic Т. The sound value of Semitic Taw, Greek alphabet Tαυ (Tau), Old Italic and Latin T has remained fairly constant, representing [t] in each of these; and it has also kept its original basic shape in most of these alphabets.

Taw is believed to be derived from the Egyptian hieroglyph meaning “mark”. Ezekiel 9:4 depicts a vision in which the tav plays a Passover role similar to the blood on the lintel and doorposts of a Hebrew home in Egypt.

In Ezekiel’s vision, the Lord has his angels separate the demographic wheat from the chaff by going through Jerusalem, the capital city of ancient Israel, and inscribing a mark, a tav, “upon the foreheads of the men that sigh and that cry for all the abominations that be done in the midst thereof.”

In Ezekiel’s vision, then, the Lord is counting tav-marked Israelites as worthwhile to spare, but counts the people worthy of annihilation who lack the tav and the critical attitude it signifies. In other words, looking askance at a culture marked by dire moral decline is a kind of shibboleth for loyalty and zeal for God.

Tav is the last letter of the Hebrew word emet, which means ‘truth’. The midrash explains that emet is made up of the first, middle, and last letters of the Hebrew alphabet (aleph, mem, and tav: אמת). Sheqer (falsehood), on the other hand, is made up of the 19th, 20th, and 21st (and penultimate) letters.

Thus, truth is all-encompassing, while falsehood is narrow and deceiving. In Jewish mythology it was the word emet that was carved into the head of the golem which ultimately gave it life. But when the letter aleph was erased from the golem’s forehead, what was left was “met”—dead. And so the golem died.

From aleph to omega / taw

“From aleph to taf” describes something from beginning to end, the Hebrew equivalent of the English “From A to Z.” Alpha (Α or α) and omega (Ω or ω) are the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet, and a title of Christ and God in the Book of Revelation. This pair of letters are used as Christian symbols, and are often combined with the Cross, Chi-rho, or other Christian symbols.

Taurus marked the point of vernal (spring) equinox in the Chalcolithic and the Early Bronze Age, from about 4000 BC to 1700 BC. Taurus was the first sign of the zodiac established among the ancient Mesopotamians – who knew it as the Bull of Heaven – because it was the constellation through which the sun rose on the vernal equinox at that time.

As this constellation marked the vernal equinox, it was also the first constellation in the Babylonian zodiac and they described it as “The Bull in Front”. The Akkadian name was Alu. Alalu is god in Hurrian mythology. He is considered to have housed the divine family, because he was a progenitor of the gods, and possibly the father of Earth.

Due to the precession of the equinox, it has since passed through the constellation Aries and into the constellation Pisces (hence our current era being known as the Age of Pisces). However, Alpha (uppercase Α, lowercase α) is the first letter of the Greek alphabet. It was derived from the Phoenician and Hebrew letter aleph Aleph which means an ox or leader. Letters that arose from alpha include the Latin A and the Cyrillic letter А.

In the system of Greek numerals, it has a value of 1. In English, the noun “alpha” is used as a synonym for “beginning”, or “first” (in a series), reflecting its Greek roots. Alpha, both as a symbol and term, is used to refer to or describe a variety of things, including the first or most significant occurrence of something.

The New Testament has God declaring himself to be the “Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end, the first and the last.” (Revelation 22:13, KJV, and see also 1:8). Omega (capital: Ω, lowercase: ω;) is the 24th and last letter of the Greek alphabet. The word literally means “great O” (ō mega, mega meaning “great”), as opposed to omicron, which means “little O” (o mikron, micron meaning “little”).

Ninḫursaĝ (Sumerian NIN “lady” and ḪAR.SAG “sacred mountain, foothill”), also known as Damgalnuna or Ninmah, was the ancient Sumerian mother goddess of the mountains, and one of the seven great deities of Sumer.

She is principally a fertility goddess. Temple hymn sources identify her as the “true and great lady of heaven” (possibly in relation to her standing on the mountain) and kings of Sumer were “nourished by Ninhursag’s milk”.

Sometimes her hair is depicted in an omega shape and at times she wears a horned head-dress and tiered skirt, often with bow cases at her shoulders. Frequently she carries a mace or baton surmounted by an omega motif or a derivation, sometimes accompanied by a lion cub on a leash. She is the tutelary deity to several Sumerian leaders.

Her symbol, resembling the Greek letter omega Ω, has been depicted in art from approximately 3000 BC, although more generally from the early second millennium BC. It appears on some boundary stones—on the upper tier, indicating her importance.

The omega symbol is associated with the Egyptian cow goddess Hathor, and may represent a stylized womb. The symbol appears on very early imagery from Ancient Egypt. Hathor is at times depicted on a mountain, so it may be that the two goddesses are connected. First Hathor, and then Isis, give birth to and nurse Horus and Ra. Hathor the horned-cow is one of the 12 daughters of Ra, gifted with joy and is a wet-nurse to Horus.

Cybele (Phrygian: Matar Kubileya/Kubeleya “Kubileya/Kubeleya Mother”, perhaps “Mountain Mother” is an Anatolian mother goddess; she may have a possible precursor in the earliest neolithic at Çatalhöyük in Anatolia, where statues of plump women, sometimes sitting, have been found in excavations dated to the 6th millennium BC and identified by some as a mother goddess.

From at least the 4th Dynasty of ancient Egypt, the sun was worshipped as the deity Re (pronounced probably as Riya, meaning simply ‘the sun’), and portrayed as a falcon headed god surmounted by the solar disk, and surrounded by a serpent. Re supposedly gave warmth to the living body, symbolised as an ankh: a “T” shaped amulet with a looped upper half. The ankh, it was believed, was surrendered with death, but could be preserved in the corpse with appropriate mummification and funerary rites.

Taweret

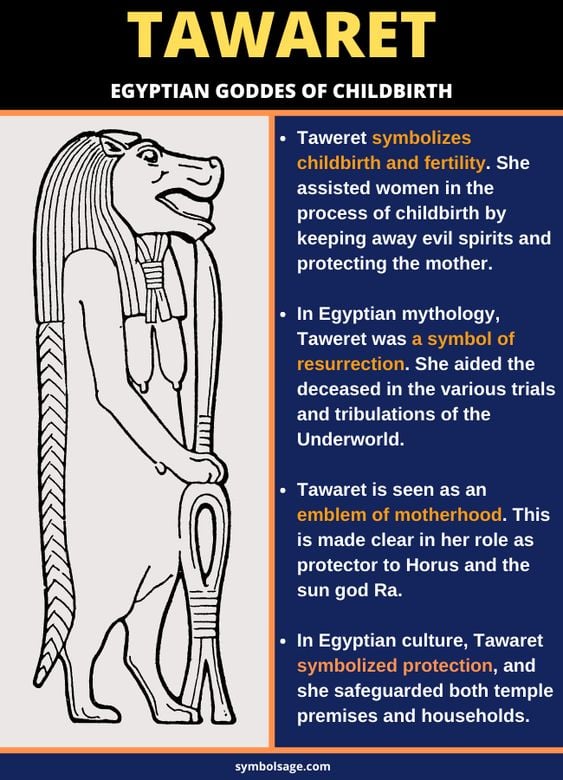

In Ancient Egyptian religion, Taweret (also spelled Taurt, Tuat, Taouris, Tuart, Ta-weret, Tawaret, Twert, Thoeris and Taueret; but also known as Ipy, Ipet, Apet, Opet, Reret) is the protective ancient Egyptian goddess of childbirth and fertility. She commonly bears the epithets “Lady of Heaven”, “Mistress of the Horizon”, “She Who Removes Water”, “Mistress of Pure Water”, and “Lady of the Birth House”.

Taweret literally means “the great female”, “she who is great” or simply “great one” , a common pacificatory address to dangerous deities, but she was also known as “Ipet” (“harem”) and “Reret” (“the sow”). At one point in history there may have been three variants of the goddess, but soon all were merged as Taweret.

She was associated with the lion, the crocodile, and the hippo; all animals which were feared by the Egyptians but also highly respected. The deity is typically depicted as a bipedal female hippopotamus with feline attributes, pendulous female human breasts, and the back of a Nile crocodile.

Archaeological evidence demonstrates that hippopotamuses inhabited the Nile well before the dawn of Early Dynastic Period (before 3000 BCE). The violent and aggressive behavior of these creatures intrigued the people that inhabited the region, leading the ancient Egyptians both to persecute and to venerate them.

From a very early date, male hippopotami were thought to be manifestations of chaos; consequently, they were overcome in royal hunting campaigns, intended to demonstrate the divine power of the king. However, female hippopotami were revered as manifestations of apotropaic deities, as they studiously protect their young from harm.

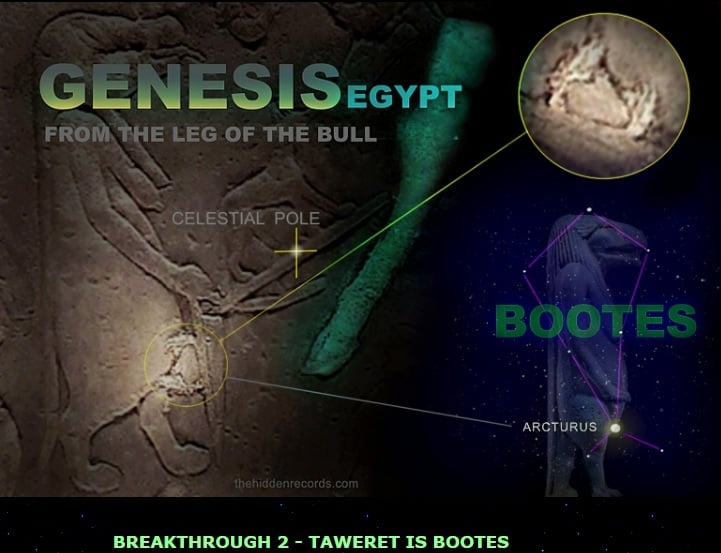

As the counterpart of Apep, who was always below the horizon, Taweret was seen as being the northern sky, the constellation roughly covering the area of present-day Draco, which always lies above the horizon. Thus she was known as Nebetakhet, the “Mistress of the Horizon”. She represented the circumpolar stars of Ursa Minor and Draco (the little dipper formed her back) who guarded the northern sky that was associated with both of the evil gods of Egyptian mythology.

The name ‘Reret’ is a shortened form of the name Taweret. Reret was also often depicted bearing a crocodile on her back. Although she is always depicted as a hippopotamus, the name ‘Reret’ means ‘the Sow’ because the ancient Egyptians saw the hippo as a water pig. Possibly the first of the hippo goddesses, she was initially viewed as a dangerous and potentially malignant force.

However, by the Old Kingdom she was seen as a protective, rather than an aggressive force (just as female hippos came to be seen as aggressive largely in defence of their young). She was thought to help women in labor and to ward off evil spirits and demons who intended harm to mother or baby.

As a result, Taweret became a mother goddess and a patron of childbirth who was often described as the mother or wet nurse of the pharaoh. As time passed she soon became a household deity, helping rich and poor alike.

Astrology

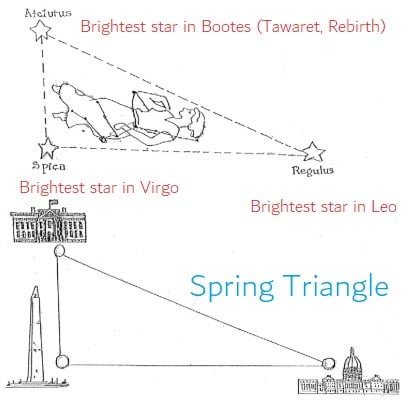

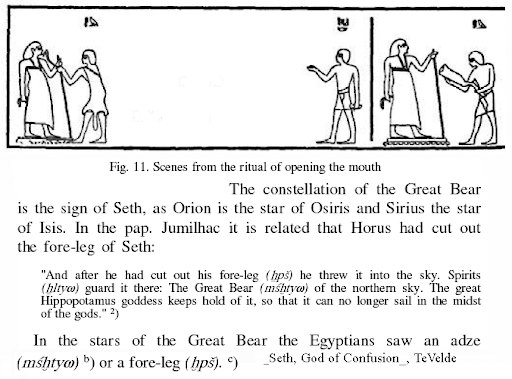

In the New Kingdom Taweret’s image was frequently used to represent a northern constellation in zodiacs in Egyptian astronomy. This image is attested in several astronomical tomb paintings.

She was thought to keep the northern sky – a place of darkness, cold, mist, and rain to the Egyptians – free of evil. She was believed to be a guardian of the north, stopping all who were unworthy before they could pass her by.

In all of the ancient Egyptian astronomical diagrams there is one figure which is always larger than all the rest, and most frequently found at the center of what appears to be a horizontal parade of figures. This figure is Taweret “The Great One”, a goddess depicted as a pregnant hippopotamus standing upright.

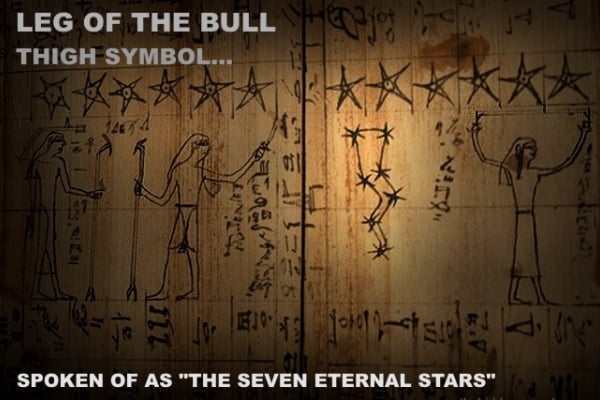

This figure represents a northern constellation associated, at least in part, with our modern constellation of Draco the dragon. She was shown to represent the never-setting circumpolar stars of Ursa Minor and Draco. The seven stars lined down her back are the stars of the Little Dipper.

In this role she was known as Nebetakhet, the Mistress of the Horizon – the ceiling painting of the constellations in the tomb of Seti I showed her in this capacity. The image of this astral Taweret appears almost exclusively next to the Setian foreleg of a bull. The latter image represents the Big Dipper and is associated with the Egyptian god of chaos, Seth.

The relationship between the two images is discussed in the Book of Day and Night (a cosmically focused mythological text from the Twentieth Dynasty, c. 1186–1069 BCE) as follows: “As to this foreleg of Seth, it is in the northern sky, tied down to two mooring posts of flint by a chain of gold. It is entrusted to Isis as a hippopotamus guarding it.”

Although the hippopotamus goddess is identified in this text as Isis, not Taweret, this phenomenon is not uncommon in later periods of Egyptian history. When assuming a protective role, powerful goddesses like Isis, Hathor, and Mut assumed the form of Taweret, effectively becoming a manifestation of this goddess.

This cosmic image continues to be seen in later periods, although the tendency was to show such divine astral bodies more abstractly. One example can be found in the late Ptolemaic or early Roman Book of the Faiyum, a local monograph dedicated to the Faiyum and its patron gods, namely Sobek-Re.

Taweret is depicted in her standard form with a crocodile on her back and a small upright crocodile in her right hand. She is shown in the section of the papyrus that is meant to depict the Faiyum’s central Lake Moeris.

The papyrus depicts the solar journey of Re with Lake Moeris as the place into which the sun god descends for his nightly journey, traditionally thought of as the underworldly realm of the Amduat. Taweret appears here as a well known constellation to demonstrate the celestial and otherworldly properties of Lake Moeris.

Chinese astrology

The Western system used Greek legends for naming the constellations, there is no overall organization of all the stars, although some constellations have linked origins such as Pegasus, Perseus and Andromeda.

The Chinese system developed independently from the Greco-Roman system since at least the 5th century BC, although there may have been earlier mutual influence, suggested by parallels to ancient Babylonian astronomy.

The system of twenty-eight lunar mansions is very similar (although not identical) to the Indian Nakshatra system, and it is not currently known if there was mutual influence in the history of the Chinese and Indian systems.

The Emperor is at the north pole, the fixed point around which all other stars revolve. Laid out underneath him is a celestial landscape broadly reflecting the layout of an imagined Imperial court. There are many more Chinese constellations (283) than in the West in smaller groups with fewer stars.

In Chinese, Běi Jí, meaning North Pole, refers to an asterism consisting of Beta Ursae Minoris, Gamma Ursae Minoris, 5 Ursae Minoris, 4 Ursae Minoris and Σ 1694. Consequently, Beta Ursae Minoris itself is known as Běi Jí èr (English: the Second Star of North Pole), representing Dì, meaning Emperor.

In Chinese, Tiān Qiāng, meaning Celestial Spear, refers to an asterism consisting of θ Boötis, κ2 Boötis and ι Boötis. Consequently, θ Boötis itself is known as Tiān Qiāng sān (“The Third Star of Celestial Spear”).

The whole sky is viewed as a scene in the heavens to reflect the organization of the Chinese nation on Earth. Around the Emperor are three enclosures. The stars in the enclosure are always visible.

The Three Enclosures (Sān Yuán) are centered on the North Celestial Pole and include those stars which could be seen year-round. The Three Enclosures are the Purple Forbidden enclosure (Zǐ Wēi Yuán), the Supreme Palace enclosure (Tài Wēi Yuán) and the Heavenly Market enclosure (Tiān Shì Yuán).

The Purple Forbidden Enclosure, which includes the pole star and parts of the constellations of Ursa Minor, Draco, Camelopardalis, Cepheus, Cassiopeia, Auriga, Boötes, and parts of Ursa Major, Canes Venatici, Leo Minor, Hercules.

From the viewpoint of the ancient Chinese, the Purple Forbidden Enclosure lies in the middle of the sky and is circled by all the other stars. It is linked to the Purple Forbidden City at Beijing on Earth. It occupies the northernmost area of the night sky. Stars and constellations in this enclosure lie near the north celestial pole and are visible all year from temperate latitudes in the Northern Hemisphere.

The second enclosure, Tai Wei Yuan, or the Supreme Palace Enclosure, covers Virgo, Coma Berenices and Leo, and parts of Canes Venatici, Ursa Major and Leo Minor. These constellations are visible during spring in the Northern Hemisphere (autumn in the Southern).

The third is the Tian Shi Yuan, or the Heavenly Market Enclosure, which covers Serpens, Ophiuchus, Aquila and Corona Borealis, and parts of Hercules, are visible during late summer and early autumn in the Northern Hemisphere (late winter and early spring in the Southern).

The Three Enclosures are each enclosed by two “wall” asterisms, designated yuán “low wall, fence; enclosure” (not to be confused with the lunar mansion “”Wall”.

The asterism Zǐ Wēi Zuǒ Yuán, meaning Left Wall of Purple Forbidden Enclosure, consists of the constellations Draco, Cepheus and Cassiopeia, while the asterism Zǐ Wēi Yòu Yuán, meaning Right Wall of Purple Forbidden Enclosure, consists of the constellations Ursa Major, Draco and Camelopardalis.

In Chinese astronomy, the main stars of Ursa Minor are divided between two asterisms: Gòuchén (Curved Array) and Běijí (Northern Pole). Northern Pole, or běi jí, is a traditional Chinese asterism found in the Purple Forbidden enclosure.

It consists of five stars found in the modern constellations of Ursa Minor and Camelopardalis and represents the five stars of the North Pole. During the Qing dynasty, a total of four stars from the constellation Ursa Minor was added to the asterism.

The modern constellation Draco lies across one of the quadrants symbolized by the Black Tortoise of the North (Běi Fāng Xuán Wǔ) and Three Enclosures (Sān Yuán) that divide the sky in traditional Chinese uranography. The name of the western constellation in modern Chinese is (tiān lóng zuò), meaning “the heaven dragon constellation”.

The Black Tortoise or Black Turtle is one of the Four Symbols of the Chinese constellations. Despite its English name, it is usually depicted as a turtle entwined together with a snake.

Furthermore, in East Asian mythology it is not called after either animal but is instead known as the “Black Warrior” under various local pronunciations. It is known as Xuánwǔ in Chinese, Genbu in Japanese, and Hyeonmu in Korean. It represents the north and the winter season.

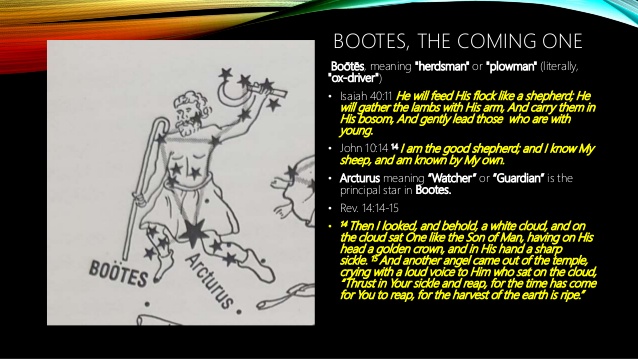

The stars of Boötes were incorporated into many different Chinese constellations. Arcturus was part of the most prominent of these, variously designated as the celestial king’s throne (Tian Wang) or the Blue Dragon’s horn (Daijiao); the name Daijiao, meaning “great horn”, is more common.

Arcturus was given such importance in Chinese celestial mythology because of its status marking the beginning of the lunar calendar, as well as its status as the brightest star in the northern night sky.

The Azure Dragon (Qīnglóng), also known as Bluegreen Dragon, Green Dragon, or also called the Blue Dragon (Cānglóng), is one of the Dragon Gods who represent the mount or chthonic forces of the Five Forms of the Highest Deity (Wǔfāng Shàngdì).

He is also one of the Four Symbols of the Chinese constellations, which are the astral representations of the Wufang Shangdi. The Bluegreen Dragon represents the east and the spring season. It is also known as Seiryu in Japanese and Cheong-nyong in Korean.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.