Horns of cattle also appear in Hemhem crown of Amun Ra and Cyrus the Great

Horned Cap

The horned cap – a cap with up to seven superimposed pairs of horns -was, from the Early Dynastic I Period onwards, the characteristic headdress of deities and heroes. The origins of the horned cap as a symbol of divinity may derive from the horns of bos primigenius, the wild cattle which flourished throughout the Near East even after the domestication of cattle. Wild cattle certainly remained extant until the Neo-Assyrian period when they were depicted as being hunted by Assyrian rulers. A large species, standing 2 metres tall at the shoulder and endowed with a large pair of sweeping horns, the wild cattle bull must have inspired considerable awe. This power explains the use of the wild bull as a literary and visual metaphor for kings and gods.

The horned cap could be shown worn by a god or man (hero), or simply by itself (often on a stand) as a seperate symbol (this usage particularly prevalent from the late Kassite period, transmitted through the Neo-Babylonian dynasty into Achaemenid Persian art, where it continued as a symbol of divinity). The style of the horned cap changed throughout time – domed or flat-topped, trimmed with feathers or surmounted by a knob or other decorative device.

A general marker of divine or semi-divine status, its employment as the symbol of a specific deity was never set. Kassite kudurrus name the cap as a symbol of the god An; by the Neo-Assyrian period, however, it had come to symbolise the national deity Aššur – three caps together frequently symbolised Aššur, An and Enlil. In Babylonia, two caps symbolised simply An and Enlil, with an occasional third symbolising Ea (Enki) in lieu of his ram-headed staff.

https://www.ancientneareast.net/mesopotamian.../horned-cap/

Distinctly pagan in their origin, and adapted to Christian use under the influence of the Church—The Roman Saturnalia—The use of mistletoe a direct legacy from the Druids—The decoration of the house with evergreens also a Druidic custom. The Christmas-tree; its introduction into England extremely recent; not universally established in Germany, the land of its origin, until the present century—References to it by Goethe and Schiller—Earliest record from Strasburg about 1600 A.D.—Theological disapproval—Theories as to its origin—Probably connected with the legend of Christmas flowering trees—Examples—The Glastonbury thorn—Mannhardt’s view; a decorated tree the recognized scenic symbol of Christmas in the paradise play of the Middle Ages, wherein the story of the Fall was dramatically associated with that of the Nativity—An ancient German custom to force into flower boughs cut on a sacred night during the great autumn festival—The date of severance delayed under priestly influence so that the boughs might flower at Christmas—Instances of the survival of this custom—The lights on the Christmas-tree a comparatively recent innovation—Legends of light-bearing trees—The lights possibly derived from ancient solstitial observances—The Christmas-tree an illustration of the blending of pagan and mediaeval ideas—A point in which the many phases of tree-worship converge

Fig. 11.—Sacred tree of Dionysus, with a statue of the god and offerings. (Bötticher, Fig. 24.)

Fig. 12.—Sacred pine of Silvanus, with a bust of the god, and votive gifts represented by a bale of merchandise and a Mercury’s staff.

(Bötticher, Fig 18.)

Fig. 10.—The goddess Nu̔ît in her sacred sycamore bestowing the bread and water of the next world. (Maspero, Dawn of Civilisation.)

Fig. 23.—Sacred laurel of Apollo at Delphi, adorned with fillets and votive tablets; beneath it the god appearing to protect Orestes. (From a vase-painting, Bötticher, Fig. 2.)

Fig. 13.—Fruit-tree dressed as Dionysus. (Bötticher, Fig. 44.)

In modern times, as the once joyful celebrations of May-day have waned the festivities of Christmas-tide have undergone increase and development. The grosser features of the festival have, no doubt, been eliminated; the mummers and the lord of misrule have for the most part gone the way of the May-king, but all the more graceful and orderly observances of the time have strengthened their hold on the popular favour. The decoration of the house is as usual to-day at Christmas as it once was at May-day, and the Christmas-tree has stepped into the place which the May-tree once held in the affections of the young. Yet if we trace these Christmas observances back to their origin, we find them as distinctively pagan in their ancestry as the festivities of May-day.

We owe the survival of many pagan customs largely to the Roman Church, whose settled policy it was to adapt the old festal rites to the purposes of the new faith, and to divert its rude converts from the riotous festivities of their unconverted friends by offering them the more orderly rejoicings of a Christian holy day. Gregory the Great, when he sent his missionaries to Britain, instructed them to Christianise 163the festivals and temples of the heathen, “raising their stubborn minds upwards not by leaps, but step by step.” And Dr. Tille, in his learned work on the German Christmas,[363] has shown what pains were taken by the priesthood to transfer to their own feast the rude rejoicings with which the unconverted Germans celebrated their great festival at the beginning of winter. The same transference of pre-Christian usages occurred in Italy, where the Christmas festival, first definitely fixed at the time of the winter solstice by Bishop Liberius, A.D. 354,[364] inherited, as expressly stated by Polydore Virgil, several of the features of the great Roman festival of the Saturnalia, held about the same time. This festival was an occasion for universal mirth and festivity. Friends visited and feasted each other, and there was a general interchange of presents, the objects presented consisting usually of branches, wax tapers, and clay dolls. The stalls were laden with gifts, like the Christmas shops of to-day. One of the days of the festival, the dies juvenalis, was devoted to children. The solstitial character of the festival is shown by the fact that another of its days was dedicated by the Emperor Aurelian to the Persian sun-god, Mithra; and Varro states that the clay dolls, which were an important feature of the celebration, represented the infant sacrifices once made to a Phoenician Baal who had been introduced to Rome under the name of Saturn or Cronos.[365]

However this may be, it is clear that some observances familiar to us at Christmas—the feasting, the present giving, and the now obsolete mumming—have an origin which is lost in antiquity. Other customs, 164too, though with a different provenance, have an equally venerable ancestry. The use of mistletoe, for instance, is without doubt a direct legacy from the Druids, who were wont at the time of the solstices solemnly to place upon their altars the mysterious branch, into which it was thought that the spirit of the tree retreated when the rest of the leaves had fallen. This practice, strangely enough, survived until within comparatively recent years in a ceremonial practised at York Minster and some other northern churches,[366] though as a rule the introduction of the mistletoe into Christian edifices was strongly reprobated, on the score that it was a heathen emblem.

The practice of decorating the house at the New Year with holly and other evergreens was also a pagan observance. Dr. Chandler refers to it as a Druidic custom, the intention being to provide the sylvan spirits with a shelter to which they might repair, “and remain unnipped with frost and cold winds, until a milder season had renewed the foliage of their darling abodes.”[367] In early times the Church made a stand against this use of evergreens as being a pagan custom, but the interdict was not persevered in, and later on we find the decoration of the churches a recognised practice, the note for Christmas eve in the old Calendar being, Templa exornantur.[368] The observance, however, which most concerns us here is that of the Christmas-tree, the evolution of which furnishes us with one of the most interesting chapters in the history of religious development. To the present generation the Christmas-tree appears such an essential feature of the festival, as celebrated in this 165country, that many will be surprised to hear how recent an importation it is. But as a matter of fact, the Christmas-tree was practically unknown in England until it was introduced by the late Prince Consort.[369] Even in Germany, the land of its origin, it was not universally established as an integral part of the festival until the beginning of the present century,[370] and it was only at that date that it came to be known as the “Weihnachtsbaum” and “Christbaum.”[371] Goethe in 1774 describes it as adorned with wax tapers, sweetmeats, and apples, but calls it simply the “decorated tree.”[372] Schiller in 1789 finds no more distinctive name for it than the “green tree.”[373] Since that time, or rather since 1830, its diffusion throughout the world has been so marvellously rapid that there is nothing to compare with it in the whole history of popular customs.

In Germany the Christmas-tree can be traced back more or less in its present form to the beginning of the seventeenth century, when an unnamed writer, in some extremely fragmentary notes, tells us that it was the custom at Strasburg to set up fir-trees in the houses at Christmas, and to deck them with roses of coloured paper, apples, etc.[374] The next mention of it occurs half a century later in the writings of Professor Dannhauer, a celebrated theologian, also living in Strasburg.[375] “Amongst the other absurdities,” he writes, “with which men are often more busied at Christmas than with the Word of God, there is also the Christmas or fir-tree, which they erect in their houses, 166hang it with dolls and sweetmeats, and then shake it and cause it to shed its flowers. I know not the origin of the custom, it is a child’s game.... Far better were it to lead the children to the spiritual cedar, Christ Jesus.” The reprobation of the Strasburg preacher was echoed by other divines, and to this cause probably the Christmas-tree owed its slow diffusion throughout Germany. The theological dislike of it, however, as it turned out, was ill-advised, for eventually the Christmas-tree displaced other popular observances of a far less innocent nature.

So far we have been treading historical ground, but in tracing the Christmas-tree still farther back we have only inference to go upon. The subject, however, has been carefully worked out by Dr. Tille,[376] and the pedigree which he traces for the tree is a most interesting one. His argument must here be condensed as closely as possible. The Christmas-tree, with its lights, its artificial flowers, and its apples and other fruit, is presumably connected with the legend of Christmas flowering trees, which was very familiar to the Middle Ages, and of which the English myth of the Glastonbury thorn is an example. The origin of the legend in Germany is thus explained by Dr. Tille:—It is not unusual when the season is mild to find trees blossoming in November, especially the cherry and the crab-tree. For the old German peasant the New Year began with the great slaughtering feast early in November, when the cattle were brought in from the pastures, and all the superfluous ones were butchered and feasted on; the winter was thus counted to the New Year, like the eve to a holy day. Hence when trees blossomed late, a casual connection was inevitably 167traced between the strange phenomenon and the New Year feast at which it took place. On the introduction of Christianity the feasts of St. Martin, St. Andrew, and St. Nicholas were substituted for the ancient festivals. The strange blossoming power of nature was connected with St. Andrew’s Day, and fruit-boughs severed on that day were believed by the people to possess particular virtue.[377] The Mediaeval Church, always eager to enlist popular superstitions in its own support, set itself to transfer to Christmas the blossoming tree of the November festival, and the legends which related how celebrated magicians like Albertus Magnus, Paracelsus, and Faustus had made for themselves a summer in the heart of winter were incorporated by the monks into the lives of certain saints.[378] The belief in trees that blossomed and bore fruit at Christmas was widely distributed and firmly held amongst the people in the later Middle Ages. In the German literature of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries many instances of the miraculous fact are circumstantially recorded.[379] A writer in 1430 relates that “not far from Nuremburg there stood a wonderful tree. Every year, in the coldest season, on the night of Christ’s birth this tree put forth blossoms and apples as thick as a man’s thumb. This in the midst of deep snow and in the teeth of cold winds.” In a MS. letter of the Bishop of Bamberg, dated 1426, and preserved in the Hofbibliothek at Vienna, the actual blossoming of two apple-trees at Christmas is mentioned as an acknowledged fact, and we find a Protestant preacher giving full credence to the belief nearly a couple of centuries later. But the most striking instance of the hold which 168such legends had taken on the popular mind is to be found in connection with our own miraculous tree, the Glastonbury Thorn—

The winter thorn

Which blossoms at Christmas, mindful of our Lord.

This tree, which was the object of such veneration in the later Middle Ages that the merchants of Bristol are said to have found the export of its blossoms extremely remunerative, stood upon an eminence near the town of Glastonbury. The legend ran that Joseph of Arimathea, who, according to monkish teaching, was the first Christian missionary to this country, one Christmas eve planted his staff in the ground. The staff, which years previously had been cut from a hawthorn-tree, at once took root and put forth leaves, and by the next day was in full blossom. The miracle was repeated on every subsequent Christmas-day. Even after the Reformation we find King James I. and his queen and other persons of quality giving large sums for cuttings from the tree, which were believed to have the same miraculous virtue as the parent thorn, and even in the following reign it was customary to carry a branch of the tree in procession and present it to the king. In the Civil War the original tree was destroyed, but some of its off-shoots survived, one especially at Quainton in Buckinghamshire, which suddenly sprang into fame again when the new style was introduced into the Calendar in 1752, and the people, resenting the loss of their eleven days, appealed from the decision of their rulers to the higher wisdom of the miraculous tree. According to the Gentleman’s Magazine for 1753, about two thousand people on the night of 24th December 1752 came 169with lanthorns and candles to view the thorn-tree, “which was remembered (this year only) to be a slip from the Glastonbury thorn.” As the tree remained bare the people agreed that 25th December, N.S., could not be the true Christmas-day, and refused to celebrate it as such. Their excitement was intensified when on 5th January the tree was found to be in full bloom, and to pacify them the authorities were driven to decree that the old Christmas-day should be celebrated as well as the new. It may be added that two thorn-trees still exist near the ruins of Glastonbury Abbey, which blossom during the winter, and are identified by Loudoun with a variety of hawthorn, the Crataegus oxyacantha praecox, which is admittedly a winter flowerer.[380]

There is, however, as Mannhardt points out,[381] another way in which a fruit-bearing tree became popularly associated with Christmas. The ancient Church had devoted the day before Christmas-day to the memory of Adam and Eve, and it was customary at Christmas in many parts of the Continent to give a dramatic representation of the story of the Creation and Fall in connection with the drama of the Nativity. Hence arose the Paradise-plays which were familiar to the Middle Ages from the thirteenth century onward. The well-known legend that the cross of Christ was fashioned from a tree which had sprung from a slip of the Tree of Knowledge served as a link between the events celebrated so closely together, the Fall and the Birth of the Redeemer, and gave additional significance to the scenery of the Paradise-play, consisting, as it usually did, of trees, or sometimes of a single tree, laden with apples and decked with ribbons. In 170some cases the tree was carried on to the stage by one of the actors. In this way the apple-bearing tree became the recognised scenic symbol of Christmas, and naturally connected itself with, if it did not spring out of, the very early legend of the Church that all nature blossomed at the birth of Christ, who Himself, according to the fanciful symbolism of the time, was the very Tree of Life which had once stood in paradise.

Another popular custom, which dates back to the time when the belief in the beneficent power of sylvan deities was general, is also probably entitled to a place in the pedigree of the Christmas-tree. It was customary amongst the ancient Germans on one of the sacred nights of the winter festival, when, according to the popular belief, nature was permeated with new life, to cut wands from the hedges.[382] These were brought home, put in water or planted in a pot of moist earth, and solemnly placed, some in the open air, some in the stable, and some in the house. A month later each wand would be in full bloom, and it was then the custom to carry it round and lightly strike with it those to whom one wished to impart health, strength, and fruitfulness. Those struck with it rewarded the striker with presents, in recompense for the benefit he was assumed to convey. This custom, which is probably of Indian origin, survived in some parts of the Continent as a child’s game even in the present century. Under the influence of Christianity the day for cutting the wands was delayed, so that they might bloom at Christmas, and in some parts it is still usual to arrange that there shall be a flowering branch in the house at that time. In Nordlingen, a century ago, families used to compete with each other as to which 171should be able to show the most flourishing branch at Christmas-tide.[383] To this day in Austrian Silesia the peasant women sally forth at midnight on St. Andrew’s eve to pluck a branch from an apricot-tree. It is put in water and flowers about Christmas time, and is taken by them to Mass on Christmas-day.[384] Amongst people to whom the apple-bearing tree of the Paradise-play was familiar the substitution for the blooming branch of an evergreen decked with fruits and ribbons and artificial flowers was quite natural. It became, as it were, a proxy for the deciduous branch, still remaining the occasion for present-giving, though now the tree became the giver instead of the receiver of gifts.

The custom of hanging lights upon the Christmas-tree is a comparatively late innovation, the well-known print of “Christmas in Luther’s Home,” where an illuminated fir-tree is represented as the centre of the festivity, being demonstrably an anachronism. The Christmas-tree, when we first definitely meet with it at the beginning of the seventeenth century, was certainly not illuminated. But the idea of a light-bearing tree was familiar to the Middle Ages. An old Icelandic legend relates that once upon a time, at Mödhrufell, there stood a mountain-ash which had sprung from the blood of two innocent persons who had been executed there.[385] Every Christmas-eve the tree was seen to be covered with lights, which the strongest gale could not extinguish. These lights were its wonderful blossoms, for in folk-lore lights are often made to represent flowers and vice-versâ.[386] In the old French legend of Perceval, the hero is represented as coming upon a 172tree illuminated with a thousand candles, and Durmals le Galois, another hero of mediaeval legend, twice saw a magnificent tree covered with lights from top to bottom.[387] It has already been mentioned that wax-tapers were given as presents at the Roman Saturnalia, and it may well be that the connection of lighted candles with Christmas time may date back to the ancient solstitial celebrations, in which they were regarded as symbolical of the new birth of the sun. The same idea—that of typifying the renewal of life by means of lighted tapers—is found in the Netherlands in connection with the May-tree, which there bears lights amongst its other decorations. At Venlo on the Maas the maidens light the tapers as the evening comes on and then dance around the lighted tree.[388] At Lüneberg, at wedding festivities, it is usual to carry a “May” adorned with lights before the bridal pair, and in the Hartz Mountains the so-called “St. John’s tree,” round which the peasants dance, is a pyramid adorned with wreaths, flowers, and lights.

In all these customs, which are no doubt survivals of the belief in a tree-inhabiting deity, we see the collateral relations, if not the direct progenitors of our Christmas-tree. In short, modern as it is in its present form, the Christmas-tree epitomises many most ancient ideas; is the point to which many streams converge whose source is hidden in a far distant antiquity. It is the meeting-point of the old pagan belief in the virtues vested in the tree and of the quaint fancies of the Middle Ages, which loved to see spiritual truths embodied in material forms. Christ, the Tree of Life, blossoming on Christmas-eve 173in Mary’s bosom; the fatal tree of paradise whence sprang the cross, the instrument of man’s salvation,—that “fruit-bearing heavenly-nourished tree planted in the midst of redeemed man,” so often represented in mediaeval art; the miracle of nature, so stirred by the wonder of the event as to break forth into blossom in the midst of winter—all these ideas, so characteristic of mediaeval thought, became grafted together with observances derived from solstitial worship, upon the stock of the sacred tree, laden with offerings and decked with fillets. Indeed the Christmas-tree may be said to recapitulate the whole story of tree-worship,—the May-tree, the harvest-tree, the Greek eiresione, the tree as the symbol and embodiment of deity, and last but not least, the universe-tree, bearing the lights of heaven for its fruit and covering the world with its branches.

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/47215/47215-h/47215-h.htm

The Origins of Santa?

St. Nicholas was a monk from a small town in what is now modern day Turkey, not far from Myra. Believed to live around 280AD, he was widely renowned for his kindness and willingness to help the poor. Eventually the idea of St. Nicholas spread to other parts of the world, each region offering an altered name. Santa Claus being a variation of the earlier Sinter Klaus, however still very similar to St. Nicholas (Saint-Nicho-las = Sant-aclaus).

Is St. Nick the true origin of Santa? Are there any earlier references to a character of a similar name, from the same area? Ancient Luwian texts that were discovered within just a few miles from the town St. Nick was from, confirm such a character. These texts predate the origin story of St Nick by almost a millennium. They mention an obscure ancient Anatolian God named Santa. He was a storm god, and a god of death, 2nd only to the main storm god of Anatolia, Tessub (Zeus). In a neighboring region's mythology (Ras Shamra Texts), Tessub is succeeded by a storm god of the underworld. This god of the underworld transitioned from a God of Death, to the beloved head of the pantheon.

Who exactly was this obscure Luwian deity? Most theologians conclude the character to be Marduk. However as referenced in the neighboring mythology mentioned, this storm god who opposed the king of gods Tessub was none other than Athtar ben Shahar (Helel). Note added: god Shahar

Sources:

Society of Biblical Literature - Iron Age Hieroglyphic Luwian Inscriptions

Society of Biblical Literature - Hittite Myths

Society of Biblical Literature - Ugaritic Narrative Poetry

Brill Publishing - The Luwian Population Groups

Oriental Institute of Chicago - Hittite State Cult of Tutelary Deities

Assyriological Studies Volume

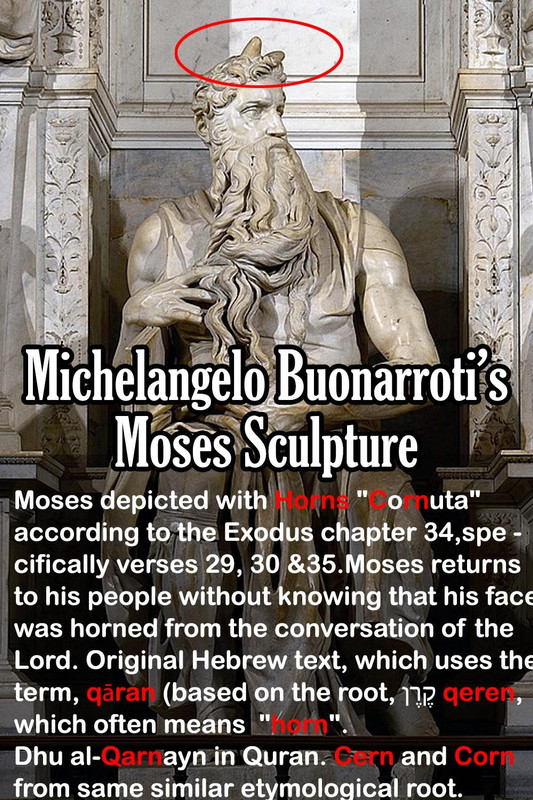

The Reason Why Michelangelo's Moses Has Horns

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.